Within the borders of the United States is a complex system of bureaucracy and jurisdictions that affects everyone living within it. Federal, state, county, and city governments cooperate, compete, and overlap. In Native American communities, tribal governments form relationships with the United States’ governing bodies around them.

Some Native Americans are part of federally recognized tribes while others are not. Each tribe has its own relationship with the other governments it interacts with, both state and federal. Federally-recognized tribes have rights to self-government that other tribes do not. States can also recognize tribes within their boundaries, though this does not grant the same right to have a “government-to-government,” relationship with the United States as a whole, Martha Salazar wrote for the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Harry Brown, an English professor with a specialty in Native American literature and the faculty advisor for DePauw’s Native American and Indigenous Association (NAIPA), said Indigenous individuals are usually “very aware” of the “contentious, complicated” relationships between tribal governments and state/federal governments. On the whole, he feels these relationships and the history behind them are “mostly invisible” to non-Native people. “Nobody's aware of these things. There's maybe a half a line in a history textbook,” Brown said.

In times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the governing functions that may be invisible or taken for granted when things are going well can also become more visible as adaptations need to be made to handle the crisis. In an email, junior Holly Buchanan, one of the leaders of DePauw’s NAIPA branch, explained that federally recognized tribes have access to funds and COVID-19 relief materials set aside specifically for them, while non-recognized tribes do not.

The Indian Health Service (IHS) is the agency “responsible for providing federal health services to American Indians and Alaska Natives,” according to their website. Tribal health services are able to determine if they wish to receive vaccines through the IHS or through associated state governments.

The IHS operates within “areas” of the country that often include multiple states. The IHS has distributed 47,395 doses of the vaccine in the Nashville area––which includes Indiana––32,228 of which have been administered.

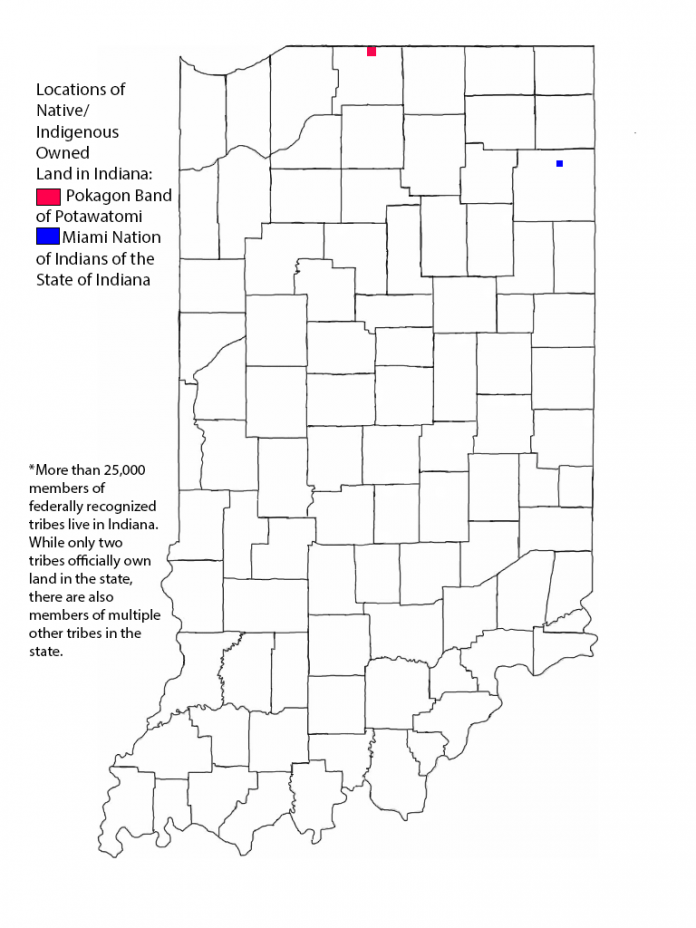

There are two tribes with land in the state of Indiana: the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi and the Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana. According to the state’s website, there are approximately 25,000 members of other federally recognized tribes living in the state. The number of individuals in non-recognized tribes is either unknown or unpublished.

The Pokagon Band has 166 acres within the state of Indiana, although the majority of the tribe’s land is actually in Michigan. According to Indiana’s preliminary vaccination plan, one-tenth of the vaccines allotted by CDC for the Pokagon Band will be sent to the Indiana State government, while the rest will go through Michigan. The two states are cooperating with each other and with the tribal government, which is in charge of distributing the vaccines to their citizens. They are currently offering vaccination to Pokagon citizens 18 years and older, as well as any none-Pokagon members of their households.

The Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana is a branch of the once-unified Miami Tribe of Oklahoma; the tribe was split by forced relocation efforts from the U.S. government, which forced part of the tribe off their lands in Indiana, while allowing some clans to remain. The Miami Nation is not a federally recognized tribe. According to their website, the tribe has repeatedly petitioned for federal recognition since 1934.

The tribe has 6,000 members and is still seeking to gain federal recognition. The tribe’s website says, “Although we have always maintained our own government and membership, sovereignty (federal recognition), would allow us to be considered an independent nation with the ability to adjudicate legal cases, levy taxes within our borders, and possess greater control over our economic development.” Due to this lack of recognition, the tribe is not able to distribute the vaccine to their citizens directly.

Brown summed up the issues of sovereignty as a question: "Do tribes have the right to make laws, enforce laws? Do they have the right to self-determination on the lands that they occupy?" He adds that economic control is also an important factor. "There's always been exploitation and poverty if the tribes don't have economic sovereignty over their own land," Brown said.

Brown connected these issues with the human rights struggles tribes have faced, including those involving the access to health care, which have been highlighted by the pandemic. He referred to the Trail of Broken Treaties, which he described as a cycle where the United States government would "make a deal" with tribal governments and then "break a deal" and repeat it. Native American and Indigenous activists both within their own tribes and working together across tribes have often focused on trying to get the United States to honor the treaties it makes. "There have been battles, many battles, in the courts waged by Indigenous groups tribally as well as nationally to correct or redress broken treaties," Brown said.

Until a tribe receives federal recognition, they do not have the legal rights necessary for self-government––which includes the right to taxation and other processes that would allow them to create and provide medical infrastructure for their citizens––nor do they have access to the resources of programs like the IHS.

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), Native American and Indigenous individuals have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and are twice as likely to die from the virus as white individuals.

Although the specifics of the vaccine rollout depend on the individual tribe, Brown has noticed one common trend. “It's not too much different from the country at large where we're giving the vaccine first to older people, but there's this sense that there's more at stake. Because on the reservations, it's the elders that… remember the traditions and the languages,” he said.

Vaccination is both essential for the protection of the individuals and for the protection of the culture and identity of the tribe, he explained, recalling Kiowa tribe activist and writer N. Scott Momaday, who believed that tribal stories are always “one breath” away from extinction. Momaday said this in the 1960s, but Brown said that it is pertinent today, especially with the vulnerability of older generations to the pandemic.

“The vaccine is a way of providing more time to pass it on, pass on the identity,” Brown said.