Last month, President Donald Trump issued an executive order requiring colleges to “certify that their policies support free speech as a condition to receive federal research grants.” Trump believes university speech codes, safe spaces, and trigger warnings are part of an effort to “restrict free thought, impose total conformity and shut down the voices of great young Americans.”

This order is the first in a series of steps the Trump administration plans to take to defend students’ rights, said Trump; however, it does not state how or by what standard federal agencies will enforce the order.

“I’m not sure of the impact it [will] have,” said DePauw President Mark McCoy. Public and private institutions support free speech because the purpose of higher education is the search for truth, he added. “We have to be able to support a diversity of opinion in order to do our jobs.”

Despite McCoy’s statement, DePauw currently holds a “red light” rating from a non-profit organization that focuses on civil liberties in academia. The rating from FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights in Education) means that it has at least one speech policy that clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech.

FIRE developed a database that ranks the free speech policies of a particular institution. Schools are assigned either a red, yellow, or green color, with red meaning that an institution has at least one policy that both “clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech,” yellow meaning that an institution’s policies “restrict a more limited amount of protected expression” and green meaning that an institution’s policies “do not seriously imperil speech.”

According to Laura Beltz, senior program officer at FIRE, DePauw’s rating is specifically due to two “red light” policies in its speech code.

One such policy, which reaffirms students and teachers are provided with an “environment free from harassment and inappropriate and/or offensive comments or conduct,” is defined too broadly, says Beltz. “Instead, the policy should ban conduct that meets the legal standard for unlawful peer harassment in the educational setting,” she said.

DePauw’s Electronic Communication and Acceptable Use Policy, banning “‘offensive … or inappropriate content,” including content that is ‘vulgar,’ ‘offensive,’ ‘promotes hate,’ or which is ‘racially inflammatory or inappropriate,’” is also deemed as a “red light” policy under FIRE’s standards. According to Beltz, “banning the mere access of things like subjectively offensive, hateful, or racially inflammatory speech includes a great deal of speech that is protected under First Amendment standards.”

Two policies are flagged with a “yellow light.” These include the Bias Incident Report Team, which does not make clear whether reports of protected speech will be investigated or punished, and the Sexual Harassment policy, which includes broad examples that could constitute harassment, but are typically constitutionally protected on their own—both policies could cause a “chilling effect,” Beltz said.

DePauw’s published commitment to the “transmission of knowledge,” the “nurturing of integrity and the cultural development of its students” is labeled as a “green light,” but “[DePauw] needs to revise its policies to meet First Amendment standards in order to live up to those promises,” Beltz said.

McCoy expressed little concern for FIRE’s rating, saying he would consider looking over policies if someone said free speech was being violated, but a “vagueness standard” from an outside organization has little agency. “We’re not in the free speech business to support FIRE; we’re in it because we’re an educational institution.”

Institutions of higher education face the challenge of allowing free expression while also keeping their students safe. “If your parents don’t think you’re going to be safe at your university, they won’t send you there,” said associate professor of communication David Worthington. But the tension between safety and free expression is not necessarily a bad thing, he added. “It’s the hopeful balance that one side isn’t being pulled further than the other.”

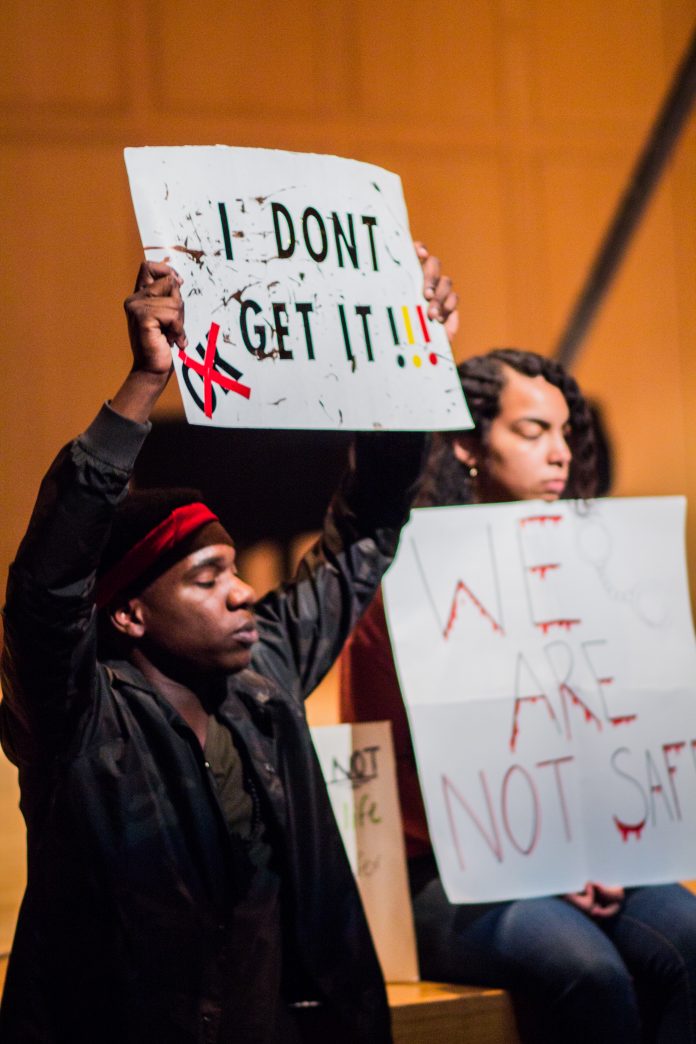

However, some scholars worry that safety has been used as a way to restrict free speech.

“We need to consider how it might be used to shut down ideas,” said professor of politics at Princeton University and author of “Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech” Keith Whittington. “We have seen it used as a reason to exclude some speakers from campus, block some topics from being discussed and exclude some ideas as unsuitable for examination, all of the grounds that such discussions will in and of themselves cause harm to some individuals and groups on campus.”

“What we care about is academic freedom,” said Whittington. Scholars should be able to research and teach on controversial issues without worry of external pressures, he added.

While the purpose of higher education is to encourage the exchange of ideas, Trump believes that “anti-First Amendment” institutions exist and claims that the executive order will prevent taxpayer dollars from subsidizing those institutions.

“I think it doesn’t apply to us,” said McCoy. He understands the order to only apply to public institutions and specifically “research-one” institutions, which the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education defines as those with the “highest research activity.”

Howard Brooks, professor of physics and astronomy and the chair of faculty, agreed, saying that it would not matter whether DePauw accepted the rules of the order or not because it gets so little federal research funding in the first place. Brooks is not aware of any free speech issues at DePauw.

DePauw has been awarded $1,177,294 in federal research grants with $477,930 currently pending, according to McCoy.

McCoy went on to say that there are some legitimate concerns about free speech on college campuses today. One of the issues, according to McCoy, is the security costs that result from hosting controversial speakers, many of which total over thousands of dollars. “If I wanted to bankrupt a poor public institution, [all I would have to do] is schedule a whole bunch of speakers that would be provocative.”

McCoy also addressed an existing concern that conservative voices are not heard as much as liberal voices, noting it as a “legitimate concern,” but he ultimately does not feel that there is silencing of speech at DePauw.

Lauren Hickey, a first-year who identifies as a conservative, believes that conservatives do not get the same treatment because they might not agree with others’ views. “I feel like our views are unsupported and not allowed,” she said. “We need to allow people to give their thought.”

Kate Hennessy, a first-year who identifies as liberal, agrees with McCoy that students with conservative viewpoints get more backlash, but Hennessy believes some of that backlash is warranted. “It’s hard to say you support women and people of color and at the same time support Trump and his party.”

Within reason, Brooks said, students should welcome opposing ideas. “As long as [someone is] not threatening you, you ought to be comfortable to hear [their opinions and beliefs.]” Individuals can disagree, Brooks added, but the disagreements should be done in a polite way.

Other than the blatant incitement of hate, Brooks believes that not many aspects of speech should be censored or limited. “It worries me that a lot of people probably don’t feel comfortable saying anything anymore,” said Brooks.

“I think the challenge we have today is: ‘How do we promote an inclusivity that welcomes everyone?’” said McCoy. “And does not further harm people who are concerned about harm.”