Across DePauw, paintings and illustrations catch fluorescent light, nestled in their frames as they have been for years since their conception or donation. Artwork pervades campus, and while it is easy to neglect in the urgency of travel, the intentions of artists from decades past are constantly transmitted into the present. Their art is patient in their tenancy of our residence halls and academic buildings, full of significance and history, ultimately deserving of a quiet, if quick, moment of appreciation.

Humbert Hall’s lounges are lined with artwork. Positioned to the right of its perpetually unlit fireplace is “Jacob Wrestling With The Angel” by David Taylor, whose class year is just as mysterious as the subjects featured in his work—it is either ‘58 or ‘59 depending on whether the paper or plaque is to be believed.

The work is enigmatic, hewed out of an angular black pit, a man and an angel striving against each other on its unmoving, yet distressed, plane. Thick, bold lines and gray values denote their identical muscles. Wings do not sprout from one of their backs, as they do in Gustave Doré’s etchings or Rembrandt’s 1659 iteration. It is difficult to tell which is Jacob and which is the Angel, perhaps in reference to the ambiguity of the Book of Genesis itself: there, the Angel is also referred to as simply a “man.” One moves to enact the touching of the hollow of the thigh—but his own. The other holds his neck in a violence so still it seems nearly tender. Taylor, it seems, may have wanted the viewer to question where man ends and divinity begins.

Other pieces in Humbert Hall are composed of similar networks of stark shapes and values. Also Biblical, Robert Hodgel’s “Gethesmane” depicts a figure—likely Jesus Christ—lying prostrate, his anguish conveyed not by his hidden face, but by the textured lines which flow out from it. The Mount of Olives juts out, Jesus and his disciples seeming to embody it, their exhausted faces shifting between stone and flesh. Even as one looks closer, the succor the Mount of Olives appears to provide weakens. Innocuous, like another fragment of stone, Hodgel has concealed the mob in the background.

Hodgel’s Jesus is oppressed by the knowledge of his impending betrayal. In his “Agony in the Garden,” El Greco instead confers Jesus with a calm dignity as the mob approaches. A sense of history is engendered in Hodgel’s work. Why, the viewer wonders, did he choose to sharpen the pain Jesus is told to have prayed for relief from? It may have been an emotional choice or simply one of instinct.

The ability of these popular subjects to be depicted in such distinct ways reveals the greater potential of all art to hold different interpretations–to be constituted by motivated choices of the artist.

In fact, there is diversity not only in what art should contain, but also how it should look. Asbury Hall’s long, nearly 100-year-old hallways, for example, are brightened by artwork popping with color.

“Carnations” by Bob Sanders was gifted to DePauw in 1983. The work is composed of featureless shapes and smooth gradients or, as on the carnations themselves, no rendering at all. They are delicate, painted in desaturated pinks and purples, overlapping as if to become one another, just as Jacob and the Angel do. The work feels anachronistic, not at all suggestive of the plaque’s unhelpful “1946” date. Its simplicity could have been generated in Microsoft Paint, while its asymmetrical balance and vacant setting are reminiscent of one of Magritte’s many versions of “The Domain of Arnheim.”

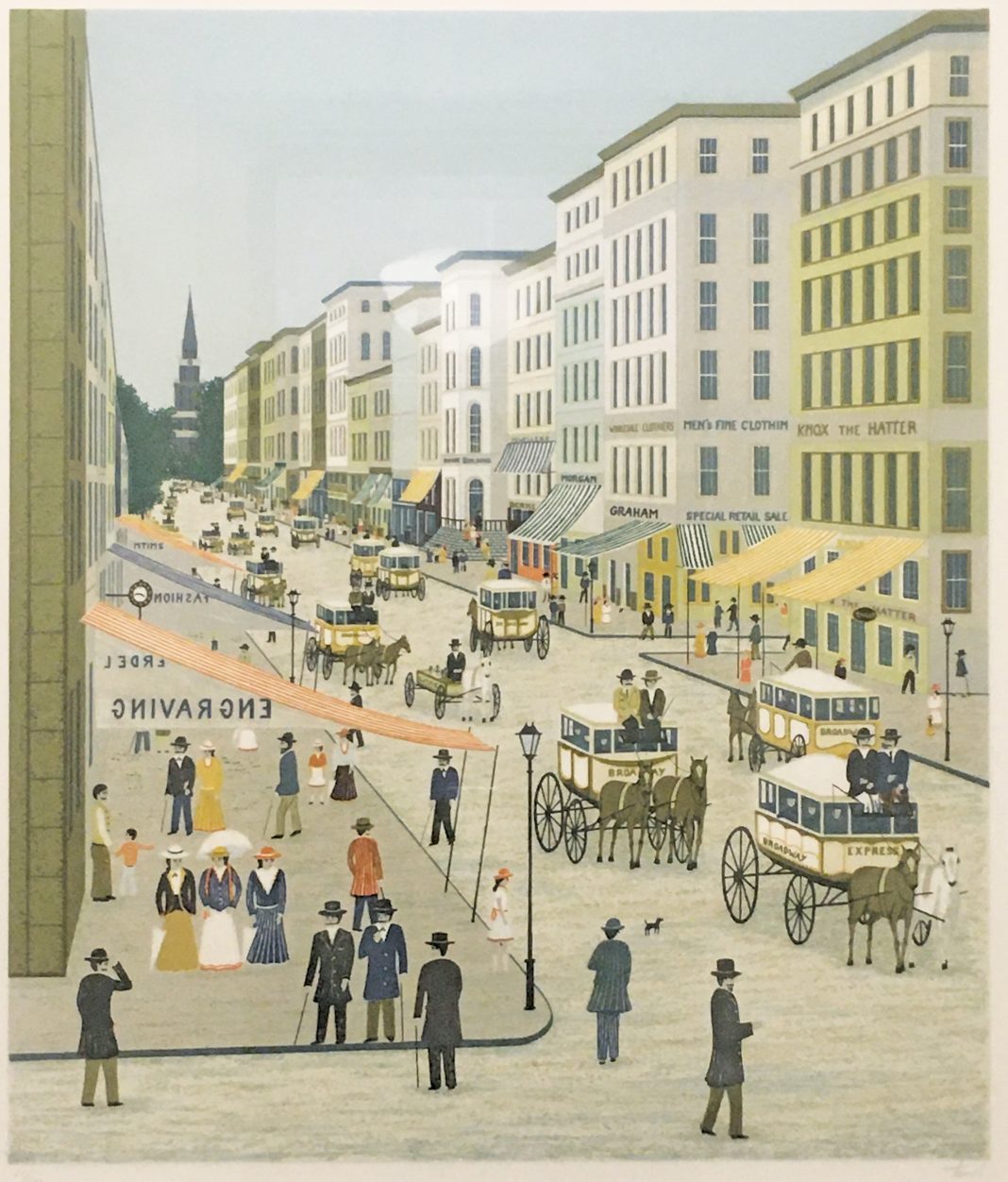

Also inhabiting Asbury Hall’s is Fanch Ledan’s “Old Broadway,” Donald Banicki’s gift in 1982. It depicts a late 1800s setting, the women in their elaborate suits and the men upright beneath their tall hats, their simple shapes walking toward the viewer out of a vanishing point. Like snowmen, dots compose their faces. The buildings, meanwhile, descend expertly into the distance with an abstract cleanliness. Rather than suggest pollution, the painting celebrates the conceptual Old Broadway’s liveliness, how there would have been Graham and Morgan, and hatters and engravers. If they used toxic materials, then that was just incidental. The painting breathes the happy air of simply being somewhere where there is movement and a companion.

Between artist to artist, the significance of art and how it should manifest shifts; from artist to viewer, significance can transform. The art across DePauw indicates various histories or perceptions we are not privy to that, regardless of our attention, are carried across decades through a series of generous acts: the initial conception, the donation, and the decision to preserve and hang the work.

What may be perceived as a deliberate choice may have been no choice at all. After all, Taylor may not have cared whether man can grade into god. Yet the difference in interpretation reaffirms the effect of even absentminded choices.

Still there are other forms of art. Pencil marks are glimpsed on the edges of desks as accounts of boredom. Chalk on walls is soon washed away, yet some faded marks will remain.

Each becomes a time capsule of ideas and emotions, continual reminders of the iterative history around us and contributed to by us.